RATED A: SOFT-PORN CINEMA AND MEDIATIONS OF DESIRE IN INDIA, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, 2024.

Darshana Sreedhar Mini discusses her book Rated A: Soft-Porn Cinema and Mediations of Desire in India with FARRAH Freibert, co-editor of Refocus: The Films of Doris Wishman (Edinburgh University Press 2021) and author of Nothing Censored, Nothing Gained: Obscenity Law and Histories of Queer Distribution and Exhibition (Edinburgh University Press, forthcoming as part of the Screening Sex book series).

Read more: AUTHOR INTERVIEW: Darshana Sreedhar Mini in Conversation with FARRAH FreibertFinley Freibert (FF): Rated A—is an incisive and rigorous multi-method intervention in not only porn studies but more broadly the field of film and media studies. The book traces the prehistory, history, and lasting impact of the South Indian soft-porn boom of the 1990s and 2000s as a significant, yet largely overlooked, media public with transnational impact. Challenging the western-centrism of much porn studies scholarship, the book counters simplistic considerations of national cinema and transnationalism by contextualizing Malayalam soft-porn as a regional and linguistically-defined media industry that has come to stand in as Indian pornography in the popular imagination. In doing so, Malayalam soft-porn is traced as a regional, transnational, and diasporic media formation produced in contexts of overseas South Indian investors and audiences. With keen originality and methodological breakthroughs, the book centers gender and labor as dual vectors of hegemonic influence out of which the South Indian soft-porn industry negotiated in not only representation but also production, distribution, and exhibition.

How did you begin working on this project?

Darshana Mini (DM): The initial thinking around this project started in 2010, as an aftermath to a focus group I conducted with teenagers to understand how they consumed soft-porn films as sex education material. In India, incorporating sex education formally into school curricula has faced multiple obstacles, both from religious groups as well as teachers’ organizations. Teachers, especially, felt that they were pressured into teaching sex-related material using safe sex paradigms, while deterrence is usually preferred in the conservative moral ethos of India. That’s what piqued my curiosity initially. As I started digging further, I realized that even though soft-porn films were widely available in cinema-halls and as DVDs, the production details of these films were not readily available. Most filmmakers and technicians who were part of these films used fictitious names in the credits. Moreover, journalistic reports spoke about these films as a den of vice, where free sex and exploitative practices were rampant, and that too warranted more investigation. I left for Chennai in 2011 to do a pilot study and to see if this is a feasible project to carry out, since getting a list of the “real names” seemed the hardest to get through. I had to wait for over two years to get my first real contact, and more time was spent in the field to track people down. After all, the filmmakers who were associated with these films weren’t always comfortable owning these films as their productions.

This project has also been about a process of patient waiting. Unlike a purely archival project or qualitative study, where you can work with a specific archive or a dataset, here the anonymity of the production practices necessitated a different model of approaching research. In many cases, it also involved waiting for clues and the right timing when the respondents would feel comfortable reconnecting back with details. This project is more than ten years in the making, and the extra time was also necessitated by the mixed methods I ended up using, including backup plans in case I hit roadblocks.

FF: I wanted to open with some discussion of the title of the book, Rated A. The introduction provides a really engaging and in-depth industrial history of censorship in India dating back to the colonial period and culminating in the rating system, the Cinematograph Act of 1952, and its amendments. It appears that the A rating came to be associated with sexual content and specifically soft-porn, especially by the time of the Malayalam soft-porn boom in the 1990s and 2000s. I am wondering how the A rating is currently perceived. Is it still mostly associated with sexual content or has it broadened in some ways? I am thinking here of how in recent times in Indian cinema there seems to be films focused more on hardboiled violence than sex that receive or apply an A rating (I’m thinking of films like Saani Kaayidham [2022] or The Kashmir Files [2022]). Would you describe such films as an exception to dominant sexual association of the A rating or has there been a shift in the characteristics associated with the rating?

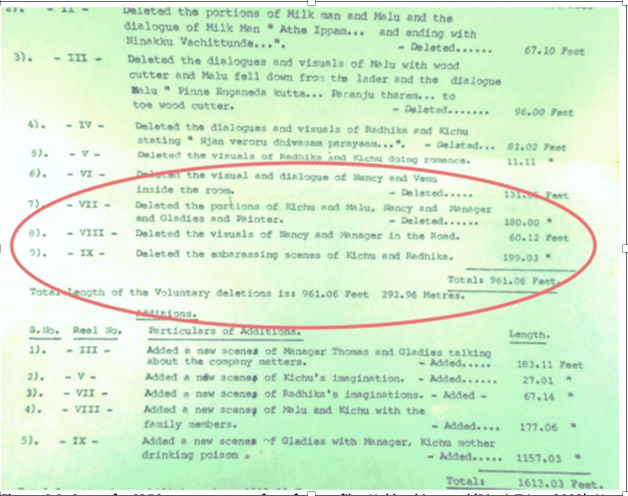

DM: In India, the A rating has mostly been associated with films that deal with sex, violence or require a mature audience to process what they see as nuanced portrayals of characters, representations and narrative arc. The certification is done by the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), a centralized body, which approves certification based on audience, after they review the film in the preview theatre. Soft-porn filmmakers knew the censorship mechanism inside-out, so much so that they started to think like the censors and predict possible scenarios where certain sequences would be muted or cuts or changes would be suggested. These mechanisms are not just unique to soft-porn, but were accentuated in the industry because of the allegedly degraded aesthetics imbricated in both its production and reception. Soft-porn films used what were called “second-writers,” who cleansed the film script of any possible contentions that the screening committee might come up with, but also left clues for the projectionist, who could add the explicit reels referred to as thundu (cut-piece) during the exhibition of the film.

As a result, many soft-porn films were rated UA (instead of A), and had generic categorizations including thriller and melodrama. Like you mentioned, violence or themes that warranted mature responses were all clubbed under the A category. So, it was not just about sex, but when we speak about A certification, sex becomes the predominant category perceived as demanding A certification, as opposed to UA (Universal certification, where children should be accompanied by adults).

Of course, the films that you mention here are also rated A—but they don’t register as “adult cinema” in the Indian imagination in quite the same way. For many people an “A” rating still immediately drums up sexual imaginaries. That said, the media landscape has gone through massive changes in the last twenty or so years, and especially now with widespread internet use and access to streaming platforms, there is much more awareness that erotic material is available, and to some extent, also accepted. That’s not to say that sexually explicit media has been condoned by the Indian state or society at large, but rather that we are in a different moment. At the time, soft-porn films and the A-rating went hand in hand in the public imaginary, and some of it was accentuated by the low-budget, and trash-aesthetics of these films.

FF: One of the central figures of Chapter 1 (and throughout the book) is Silk Smitha, who, as you argue, came to retrospectively emblematize the South Indian soft-porn industry, and the associated figure of the madakarani, despite the fact that her films predate the Malayalam soft-porn boom. What would you say sparked the retrospective claiming of Smitha as an originary figure in soft porn? Was this because her death coincided with the beginnings of the soft porn boom in the 1990s and people recognized her formative influence on the genre, or was there some other impetus for this reclamation?

DM: The retrospective stardom of Smitha extends and expands the scope within which sexual excess was imagined in the screen-pleasures provided by these films. Smitha entered the film industry as a touch-up artist, and later as a dancer-actress. The sexualized and eroticized roles that she donned in films aligned with the features attached to the figure of madakarani— as a sexually autonomous woman who uses her sexual charms for upward social mobility. This takes various forms, including sexual self-fashioning, engagement with open relations with the opposite sex, or situations that suggest intergenerational desire. In the case of Smitha, the onscreen roles she enacted became etched onto her body as if it were a second garb. Film journalistic accounts made it doubly visible by including her images as centerspreads and circulating sensational reports that denied her agency and voice.

I think Smitha’s eroticized roles were incorporated into the pantheon of films that came as part of the soft-porn wave in the 1990s. Films like Layanam, which was made in the 1980s, were retrospectively folded into this pantheon as a soft-porn film. The categorical distinction of soft-porn became hinged on the figure of the strong female leads in the cast of madakarani, and Smitha’s earlier films came to be seen as precursors or progenitors of the soft-porn wave—but the historical timeline became blurry later on as soft-porn films circulated throughout India as dirty pictures from “the South” of the country. That, I think, is where the confusion begins. This also had to do with the popular portrayals of Smitha’s “mainstream” failure as a result of her reputation as a dancer and then as a madakarani figure. All of that stereotyped her as a “soft-porn” actress posthumously, even though that characterization is anachronistic.

FF: Could you say more about the class and caste dimensions of the madakarani? Are there particular filmic signifiers of caste such as costume design or performance that signal a film characters’ caste to audiences, or are audience perceptions of soft-porn or glamour film stars’ caste more based on biographical details circulated in the press? How does caste operate in the viewer perception of Shakeela, or is her stardom understood by audiences only through the lenses of class and religion?

DM: The madakarani’s body was marked by caste and class markers, which imposed a certain veshyatvam (profligacy), marking them as distinct from the mainstream actresses who were expected to attune themselves with middle class moral values. This went hand-in-hand with concerns that sex workers have infiltrated the film industry and that there have to be checks and balances in place to facilitate the entry of women from middle class families who can bring respectability to the industry. More than a representational trope, I consider madakarani to be a figure who unsettles social mores about heteronormativity. The question of caste I think operates at two levels: on- and off-screen.

First, there is the off-screen, wider social reality of caste. The biographical details of the actresses were not widely publicized except their first names, with no last names. The caste backgrounds were not known from the first go but, from my research, I was able to get data on the fact that there were many women from caste-oppressed communities, but some from upper-caste backgrounds were also part of this group. Many of these women had come to Madras (now Chennai) to explore their prospects in making it to the mainstream industry, and when things didn’t work out, they went for other ways to keep up their chances to stay in the industry. Many of these madakarani figures were not homebred actresses from Malayalam cinema, and came from other states like Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and some even from Hindi. So there was an “elsewhere” that was coded into the way film journalistic discourses looked at them as newcomers in transit, who might stay in the industry to look out for jobs, and then disappear to be heard of no more. Shakeela, who became the mascot of the soft-porn industry came from a Muslim family of Tamil-Telugu origins, and her success was attached to the outsider status she occupied in the industry.

To go back to the question about caste-as-representation, these films were not always explicit about caste. But caste always operates at visible, as well as invisible levels. There were a range of religious identities that these characters were designated, which included Hindu, Muslim and Christian identities. In many cases, caste identities, even when not named can be inferred from socially learnt cues—as for example when madakarani representations center on specific communities. Often Shakeela herself would play characters that would be embedded in social matrices such as tea-garden labor communities, or alcohol sellers. Socially, these are not “upper-caste” designations, and so the representations also centered these characters as sexually available for middle-class, upper-caste men. But again, such representations are not the only kind of representations in soft-porn. Without being cued into the social clues and the knowledge about how caste operates socially, in many cases even caste-specific representations can come off as “casteless” as these films circulate.

FF: In Chapter 1, you mention that Silk Smitha worked in several linguistically distinct film industries (Kannada, Tamil, Telugu, and Malayalam) and also that her films were dubbed into Hindi. Is or was such multilingual work common for South Indian actresses, or was Smitha’s multilingual work a function of her popularity? Was it common practice that South Indian language films be dubbed into Hindi (or other languages), or was this also due to the popularity of Smitha’s films? Relatedly, since she only retrospectively came to be a soft-porn icon, what were the associations of her films at the time of their original release. For instance, were these considered somewhat mainstream melodramas, or did they have a B-grade sexual association similar to later soft-porn films or glamour films? Were the historical audiences for her films likely to be predominantly men, or is there a possibility that there were women who were fans of her films and her stardom in general? Do the re-release of her films on platforms like Eros Now provide possibilities for new fan formations around Silk Smitha?

DM: Smitha acted across different language industries and her dance numbers had such an appeal that they were added as extraneous strips using film cement by exhibitors to low-performing films to attract audience. She was popularly referred to as the “Helen of South India,” referring to Helen, the Burma-born Indian actress who was a sensation in the 1970s Hindi cinema. These films were categorized as melodramas and thrillers and were united by the low-brow aesthetics, as well as investment in the erotic potential offered by the female lead heroine who was cast in the mold of madakarani. It’s also important to remember that these were not the only kind of films Silk Smitha acted in. Her filmic oeuvre was much wider, and she also acted alongside mainstream superstars such as Kamal Hasan, and with respected directors such as Balu Mahendra, so her films would have been seen by different categories of audiences and different demographics—men and women included. However, in public memory, the erotic overshadows all of this. The re-release of these films in Eros Now has not provided much fan-mobilization, but then again, Silk Smitha has never really disappeared from the public imaginary. That said, re-releases and digital circulation certainly allows for a closer analysis of these films which are otherwise available only as DVDs or on platforms like YouTube.

This goes beyond Silk Smitha and applies to soft-porn more specifically as well. The very fact that you now have multiple versions of the films, with different additions and subtractions from what you have watched in the cinema hall really helps to understand soft-porn films as being subjected to an unstable regime of operations where different stakeholders, censor script writers, projectionists and DVD transfer agents have worked collectively to produce various affects. Many of these films were categorized as melodramas or thrillers, with a good number of vendetta narratives showcasing the woman avenging the men who have betrayed their trust or subjected them to violence. In the thematic preoccupations, Malayalam soft-porn also aligned with the low-budget films made in Hindi by filmmakers like Kanti Shah, Kishan Shah, J. Neelam and others who made films in the 1990s and 2000s. Unlike the prominence of horror genre in these Hindi low-budget films, most of the Malayalam soft-porn were geared towards melodrama and thriller. Even though these films had a predominantly male patron-base, in my interviews, I also spoke with women respondents who had accessed these films as DVDs and videos that were available in lending libraries. Many of these films were also telecast during late-night telecast in the satellite channels like Surya TV as a part of “Midnight masala” and in local cable television, where there were patrons who used to call in to request these films for the late-night slots.

FF: In terms of Indian cinema’s preservation and re-release of older films, I’ve noticed regarding Hindi-language cinema that there seem to be two tendencies: releasing ‘classic’ films of auteurs and also releasing popular genre films. Specifically, in addition to auteur-driven classics like some of the films of Raj Kapoor or Guru Dutt, which have been restored for high definition release on Blu-ray and streaming platforms, there seems to be a tendency toward restoration and re-release of popular genres such as action (like Deewaar [1975] and the forthcoming Sholay [1975] on Blu-ray) or horror (with the international Blu-ray release of some of the Ramsay Brothers films). Since soft-porn film is a type of popular genre cinema, like horror or action, which seem to have a devoted fanbase that might spark retrospective interest or nostalgia (as you describe in Chapter 5), do you think there is any chance of South Indian softcore films of the 1980s, 1990s, or 2000s being restored and re-released on streaming or even physical media formats? What were the films that could be considered the most popular or representative of the soft-porn genre form the 1980s to the 2000s?

DM: So far, there haven’t been any re-release or restoration of soft-porn films since they are still relegated to the margins of respectability. The re-release is pivoted towards the category of popular films, which intersect either with art cinema/popular cinema, or for films that have accrued cultural value over the years as let’s say, the “cult value” accorded to some kinds of low-budget horror films. Soft-porn films do not fit either of these categories, since it inhabits the zone of degraded aesthetics and production practices that are devalued in film industry discourse. It’s not that there aren’t iconic soft-porn films, but rather that there’s a certain kind of pretense that these films didn’t exist…even though their circulation and impact is widely known about. To this day, soft-porn films are more the stuff of locker-room talk or private banter, rather than public acknowledgement.

Many of these films were quite impactful at their time. Two films come immediately to mind. Aadyapaapam (P. Chandrakumar, 1988) is slightly before the “real” soft-porn boom, but it opened up many doors. It was based on the Adam and Eve story and featured full frontal nudity, but this was a film that showed later soft-porn filmmakers how to take advantage of different kinds of financial schemes, censorship loopholes, and regional-language markets through dubbing practices. The other, and perhaps the most iconic example, is Kinnarathumbikal (R.J. Prasad, 2001) starring Shakeela. At one time this was also telecast on Asianet—a prominent Malayalam television channel which caused quite a furor. But that telecast itself was an event that is remembered to this day when people invoke the popularity of soft-porn cinema.

But, as I argue in Chapter 5, there is a different form that this cultural nostalgia takes. There are most likely not going to be re-releases of soft-porn films anytime soon, but the memory of these films still lingers in the cultural imagination manifesting in certain kinds of representations. There is a proliferation of films that address soft-porn as a temporal marker of the 1990s: (Classmates (Lal Jose, 2006), Ore Mukham (Same face; Sajith Jagadnathan, 2016), Pavada (Skirt; G. Marthandan, 2016), Parava (Birds; Soubin Shahir, 2017), Rosapoo (Rose; Vinu Joseph, 2018), and Super Deluxe (Thiagarajan Kumararaja, Tamil, 2019). But there are very few films which attempts to critically engage with the form, its historical arc and exhibition strategies— like Kanyaka Talkies (K. R. Manoj, 2013). Showcasing the transformation of a soft-porn theatre to a church, Kanyaka Talkies captures the tense negotiations between religion, affective regime of sexual excess and the collective memory over spaces that has doubled up in various capacity as sites of desire and piety. The multi-media installations made by the artist Priyaranjan Lal that formed part of the film, as well as exhibited separately, offers a critical framing of the impact the images had on the viewers. These include an installation that had hundred bath scenes from various soft-porn films viewed through a peep-holes, another installation that showcases faces of actresses who were cast as madakarani on cylindrical posts that were lit from inside and finally, a multimedia projection of animated images that showcases Shakeela, Silk Smitha, Reshma, Maria and others, riding a horse, with their faces change as the horse gallops along, drawing from Eadward Muybridge’s photography. I think it’s in these revisitations of the soft-porn genre that we see the engagement with the form more strongly as it intersects with collective unconscious of the viewers.

FF: Throughout the book, various media formats of distribution (such as film, U-matic, Betamax, VHS, DVD, VCD, streaming platforms) are mentioned as avenues that soft-porn has taken in different historical moments. Since you locate the historical origin of the Malayalam soft-porn boom in the late 1990s/early 2000s, which is the time of industry transitions from analog formats to the dominance of DVD (and to some extent VCD) I was wondering if you could describe some of the specifics of distribution during that era. For instance, was the typical distribution timeline for soft-porn films involving initial theatrical exhibition, then subsequent release on VCD and/or DVD, or were films sometimes distributed simultaneously to theaters and on consumer video formats? What would be the difference between the markets for VCD versus DVD in the soft-porn context?

DM: Various media formats were used in soft-porn distribution as it crisscrosses different time periods and historical moments, from what we can think of as the “proto-soft-porn” glamor films of the 1970s and 1980s, to soft-porn proper that emerged in the mid to late 1990s. Between the 1970s and the 2000s, the films were made in celluloid and circulated mostly as 35 mm prints. The exhibition of these films was accompanied by insertion of thundu (cut pieces) which involved sexualized sequences, shot separately. In the s1980s, it took the form of VHS and VCD, prominently imported via Southeast Asia and the Middle East Gulf countries.

As I argue in my fourth chapter, the transnational journey of soft-porn was also supported by the import of the NRI films—films imported by the Non-Resident Indians to India, supported through the government’s need for inviting more foreign exchange to India. These films took the form of sex education film packages, with a mix of Swedish, Danish and American hygiene films. Like in the U.S, video was predominantly associated with the spread of sexually explicit material, and there were raids and police surveillance to weed out pirate media, of which porn was seen as a prime example. There were video parlors and libraries that screened video porn. The inside room behind the main video parlors were used to screen porn films to selected patrons. Soft-porn took the form of DVDs when they were exported to the Gulf through pirate and underground channels, where they became part of migrant media assemblages. VCD were popular among the Gulf migrants whom I interviewed, while the DVD was part of the home consumption of these films.

So in terms of “soft-porn proper” we are looking at a distribution cycle that begins with 35mm (and variations of these reels with different kinds of cut-pieces). As an intermediate stage you would have VHS and then CD/DVD circulation, which in many cases would operate through a gray market and the gray market actually makes it hard to track a proper distribution cycle which is possible for mainstream films with box-office records, documented distribution deals, trade records etc. Finally, or simultaneous to these, would be the contraband circulation of these films among diasporic audiences, mostly in the Middle East. This is even more difficult to track for obvious reasons.

FF: Chapter 3 centers on the precarious star image of Malayalam soft-porn icon Shakeela, expanding on the work from your article in Feminist Media Histories. I was particularly fascinated by your discussion of her allyship and forging of alternative kinship with the transgender community. It reminded me of a concept I’ve discussed called “solidarity stardom.” I was wondering if you could speak a bit more about when and how knowledge of this allyship circulated publicly. Was this at the beginning of her career, in the middle of the soft-porn boom, or after the soft-porn boom? How did journalistic discourse frame this allyship (was it in a sensationalistic way or in a sympathetic light)? How (if at all) has her allyship with the transgender community affected her audiences and the fandom around Shakeela? Do you think she has cultivated a queer or trans audience for her films as a result?

DM: Shakeela’s allyship with the trans community became more visible after the soft-porn boom. What I appreciate in her interviews is the way she sees this as a way to opt her own family, as opposed to the biological model of blood relations. For someone whose image has been so integrally connected to heterosexual fantasies, I found her own interventions to think about heteronormativity fascinating. I think her own minoritized experiences being a Muslim woman who became part of the soft-porn industry, and as someone who became a target for women’s groups who alleged that her films peddled obscenity, made the allyship stronger.

In fact, the media was quite sympathetic and supportive towards her efforts and her fan base also increased after she appeared in the reality television program Big Boss—a platform that also allowed for her to speak about her queer allyship. After the soft-porn wave was over in 2010s, Shakeela hosted sex-education programs in Tamil television, and later became part of a promotional sketch to speak about consent as a part of the Netflix series Sex Education.

Your use of the phrase “solidarity stardom” in the instance of Judy Coleman’s interventions in the coalitional space to bring community together resonates with some extent with Shakeela’s activist work. Since 2021, Shakeela has joined the political party, Indian National Congress and her social media pages curate her commitment to intervene in injustice meted out to disadvantageous communities. Like Coleman, in the case of Shakeela, the narrative about her rise from “ordinariness” was emphasized in the modest family background that Shakeela grew up in, acting in her first film made by a neighbor (a make-up-man in the film industry), and her later rise as a marketable star who emblematized soft-porn films, so much so that they were called “Shakeela films.” So there are a lot of intersecting narratives that recraft her image in this activist that foregrounds her commitment towards transformative justice.

FF: A couple times in Chapter 3, you mention the obscenity cases against Shakeela. This reminded me of some of my own research on obscenity cases in the US. Would court cases be public record in South India, and if so, would the case files for these be very difficult to find? As a comparison with journalistic discourse on these court cases, what different or similar insights might court records offer for research on Shakeela?

DM: Obscenity cases are heard by the trial courts. But getting hold of the documents has not been an easy task. I managed to get a few, but these were limited to quashing of cases for lack of evidence. I also looked at legal cases that were part of the raids on cinema halls and how actors who were part of the film were charged with obscenity. In a couple of instances, cases against Shakeela were charged for the films where thundu (cut-pieces) were added, even though she doesn’t appear in any explicit scenes in the film. Obscenity is filtered through the moral lens of destabilizing familial values by encouraging libertine sexual values. The journalistic reports provide only sparse details and in accessing legal documents, I mostly have to rely on the judgement copies.

FF: There were some fascinating observations throughout the book where you drew links between soft-porn and political scandals, and there were also historical incidents you described where seemingly grassroots activists protested soft-porn exhibition and production. The introduction in particular traces the history of censorship in India and how sexual representation was often associated by censors with South Indian cinema, for instance, you discuss the resignation of the CBFC chair Vijay Anand. In terms of politics, in some countries like the US, Canada, or UK antipornography rhetoric is often used as a tool for specific ideologies or parties to gather political clout, particularly right-wing politicians. Is there a similar history of the politicization of pornography and censorship in an Indian, or even specifically a South Indian context, or is there more of a political consensus on the subject between the left and right?

DM: In India, the Information and Broadcasting Ministry is charged with screening media material that might upset the sentiments of people who are exposed to it. So there is an imposition of the culture of hurt, whereby anything that goes against the middle-class, bourgeoise value system can be banned or protested against. CBFC is the government appointed board, and it reflects the ideological bent of the political dispensation. Pornography happens to be the one topic for which there seems to be a consensus among different political parties on the outright need to ban it from the public space.

To a large extent, obscenity laws in India in the late 19th century were shaped by the colonial intervention to contain sexuality. An obscene object is defined as any object that can corrupt the sensibility of the person who is exposed to it. Anything that veered away from normative sexual practices automatically became part of this sexual regulatory framework. We see the politicization of pornography in the 1990s with the anxieties around economic liberalization that opened the markets to foreign products and media, as well as in the debates around trafficking and sex work. But across the board, pornography never became part of the free speech discourse unlike in the U.S context.

Dragonflies, R. J. Prasad, 2000) (left) and trailer at The Lost Entertainment

(right). The woman-on-top position is a distinctive marker of soft-porn films.

FF: There is a fascinating quote at the ending of the book related to the concept of national cinema where you suggest that Malayalam soft-porn might be considered a kind of national or “Indian” pornography. I took the quote to mean that, on one hand, mainstream Hindi cinema is largely perceived as “Indian” cinema thereby situating Malayalam cinema as a kind of minor or subnational or regional cinema, on the other hand, it is Malayalam soft-porn that comes to mind when people think of “Indian” pornography. You write: “In mapping these narratives, my work has been invested in examining a genre that emerged outside the framework of national cinema and the imagined national cinematic center—Bollywood. Curiously, as this book has shown, Malayalam soft-porn came to define the imagination of ‘Indian’ pornography across the country and in places such as the Middle Eastern Gulf ” (171). I wonder how you might situate Hindi softcore (such as some of the films of Kanti Shah) in relation to the fact that Malayalam soft-porn stands in for “Indian” pornography? Would a typical consumer consider Hindi softcore to be a kind of minor or specialty subcategory in relation to Malayalam soft-porn, or are there slippages or equivalences between the two? From an industrial standpoint how do Hindi softcore and Malayalam soft-porn compare in terms of their claim on the market? Are they fairly distinct or if they are in direct competition does one dominate the other in a business sense?

DM: In one of the recent articles that I co-wrote with Anirban Baishya, we look at the mainstreamization of discussions on pornography looking at the reality program Cinema Marte Dum Tak (Vasant Bala, 2023) produced by Vice that investigates the marginal production practices, including films that came under the broader category of Hindi soft-core, produced by Kanti Shah, J. Neelam and Vinod Talwar. The series attempts to recuperate the labor that went into the making of the Hindi low-budget films of the 1990s and early 2000s, by bringing the filmmakers and their crew to the limelight by giving them money and resources to making a representative film that resonates with the 1990s phase. Interestingly, the series doesn’t refer to Malayalam soft-porn or the regional variations of these films found in other language industries, by making it an exclusively “Hindi” language film production phenomenon. I think similar production practices of using low budget to support B-circuit and C-circuit cinemas have happened in Hindi, as well as other language cinemas.

My attempt to use Malayalam cinema as a case study in Rated A is also to demystify the way Hindi cinema becomes the epicenter to understand production cultures in Indian film scholarship. What would happen if we considered Hindi low budget cinema as one of the variations of Malayalam cinema, as opposed to imagining the latter as a regional variation of Hindi cinema (a claim that Cinema Marte Dum Tak takes in focusing on this as a Hindi language phenomenon)? The hierarchy of knowledge formation in Indian cinema scholarship, and how Indian cinema is perceived by the West, is premised on a master-text of Hindi films, and the rest of India as substrata that are constantly trying to “catch up” with the national cinema—Ashish Rajadhyaksha calls it the “Bollywoodization of Indian Cinema.”

In this project, I was keen to use “Malayalam soft-porn” as a phrase to indicate that there could be more productive ways of addressing questions around respectability, sexuality and obscenity. But we have to think of these within a longer duration and take a broader look. Forms of media making including erotic pulp fiction, sensational magazines and confessional narratives purported written by sex workers—some of which pre-existed soft-porn as a form of industry category—are perhaps more influential in the case of Malayalam soft-porn cinema than the films of let’s say Kanti Shah borders on the soft-core, but is perhaps not remembered as a “soft-porn” filmmaker as let’s say someone like Shakeela who is only thought of as a “soft-porn” actress.

FF: What do you see as the future of Malayalam soft-porn studies and history? Are there any online distributed pornographies from South India or other regions in India or transnationally that are emerging in the contemporary moment that compete with the spaces claimed by Malayalam soft-porn on streaming platforms and tube sites?

DM: I think there is still a delegitimization of studying cultural objects which are perceived as morally questionable. Discourses around porn reveal deeper anxieties around relationship between sexuality and social order. Especially when you speak of female sexual pleasure and women centered narratives that these films foreground, there are still qualms from certain quarters of feminist intervention on why sexual explicitness has to be studied on its own terms. For me, gender non-normativity is the crux of soft-porn’s intervention. It showcases women who wanted to expand the envelope of what counts as desire outside heteronormative relationships, women having relationships with younger men, and self-fashioning through engaging in sexual exploration. I think the pushback against soft-porn also came because of its ability to upset and unsettle social codes of morality, at the same time appeal to the deepest desires that was hidden in the collective psyche. As Laura Kipnis argues, there is a “hierarchy of legitimacies” within which sexual content is evaluated, and the more it upsets class distinction, the more it is subjected to control and censuring. I think this also filters down to academic spaces and the perception of “porn studies” as “porn itself” more widely—not just in the case of Indian/South Asian/Malayalam studies of pornography.

I have had many PhD students ask if they would face challenges in the job market for a project that looks at adult media. When I started this project in 2011, there were not many people working on adult media in a South Asian context. The only book that addressed adult cinema was Lotte Hoek’s Cut-Pieces: Celluloid Obscenity and Popular Cinema in Bangladesh (2013). It was my chance encounter with SCMS’s Adult Film History Special Interest Group that gave me an anchoring in exploring shared interests and a supportive community. Since then, I was able to build camaraderie with South Asian scholars who were interested in doing porn studies. I co-edited two special issues of Porn Studies themed on South Asian pornographies—a labor of love—which featured articles by a mix of senior scholar and graduate students that expanded the scope of what counts as porn studies in the South Asian context.

The scope of porn work, and subsequently porn studies in South Asia has expanded to camming and erotic performance, digital intimacies, and hook-up culture. In short, I am excited to see vibrant scholarship emerging from young scholars in the field that is extending what porn studies can become outside the Euro-American contexts.

CONTRIBUTORS

Darshana Sreedhar Mini is Assistant Professor of Film at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, author of Rated A: Soft-Porn Cinema and Mediations of Desire in India and co-editor of South Asian Pornographies: Vernacular Formations of the Permissible and the Obscene.

Farrah Freibert is Assistant Professor of Media Studies at Southern Illinois University. She is co-editor with Alicia Kozma of Refocus: The Films of Doris Wishman (Edinburgh University Press 2021) and author of Nothing Censored, Nothing Gained: Obscenity Law and Histories of Queer Distribution and Exhibition (Edinburgh University Press, forthcoming as part of the Screening Sex book series).